The territory of present-day Tajikistan was part of the Iranian Empire, the religion of which was Zoroastrianism.

When the Iranian Sassanids were defeated by Umayyad Arab armies in 636, Islam was gradually spread throughout the Central Asian region. See Archaeology and History.

The religion of the vast majority of Tajikistan’s population today is Sunni Islam. In the Pamirs, however, a majority of the people profess the Ismaili faith (i.e. are followers of the Aga Khan). According to local tradition, the Pamiris were converted to Ismailism in the 11th century by the Persian poet, traveller and philosopher Nasir Khusraw. However, one of the foremost non-Ismaili authorities on Ismailism, W. Iwanow, of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, writing in 1948, expressed the opinion that “the present Shughnis, Wakhis and others were not yet settled there in Nasir’s time. They came to that locality much later on”. See “Nasir-I-Khusraw and Ismailism” on https://www.ismaili.net/Source/khusraw/nk2/8.html.

The website of the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London contains much interesting information on the history of the Ismaili community. See, for example https://www.iis.ac.uk/view_article.asp?ContentID=105073.

One of the most important repositories of the culture of the Pamirs is the traditional Pamiri house, locally known as ‘Chid’ in the Shughni language. What to the untrained eye looks like a very basic – even primitive – structure, is, for the people who live in it, rich in religious and philosophical meaning. Tajik writers consider that it embodies elements of ancient Aryan and possibly Buddhist philosophy – some of which have since been assimilated into Pamiri traditions. The symbolism of specific structural features of the Pamiri house goes back over two and a half thousand years and its distinctive architectural elements are found in buildings in several other areas close to the Pamirs. See here for more detailed information on the symbolism of the Pamiri house.

Pamiri handicraft skills are being revived by a project of the Aga Khan Foundation, with support from the Christensen Fund and Aid to Artisans. See here.

Typical Pamiri handicrafts include: beautifully decorated skullcaps, surrounded by a woven band containing Zoroastrian symbols, decorative embroidered cloths (suzanis)

Photos courtesy Robin Oldacre

and knitted socks and gloves in bright colours

See https://thebootstrapproject.com/blog/view/102 for another interesting project aimed at revitalising the production of suzanis.

Old Pamiri jewellery can still be found, comprising primarily necklaces made of coral with silver decorations and rings with spinel stones (reportedly, the coral is found in the hills of the Alichur plain and is there because this whole area was raised from sea-level to its present height as the continents drifted and tectonic plates clashed).

There is a saying in Tajikistan that the people from Leninabad govern, those from Kulob fight, in Garm they pray – and the Pamiris dance. Certainly it is difficult to imagine life in Gorno-Badakhshan without the perpetual accompaniment of music and dancing. Every village has excellent musicians, young and old as well as expert dancers. Men and women dance together, although there is no contact. Women perform as solo singers and occasionally as accordion players.

A traditional welcome to Pamiri villages is often performed on the daf (flat tambourine-type drum) by women in complex rhythmic patterns. These performances are mostly by older women, which suggests that the tradition may be in danger of dying out.

A “Roof of the World Festival” is organised annually in the Pamirs. A superb film of the 2009 edition by Matthieu and Mareile Paley can be found here. It includes much music and dancing as well as performances on the daf.

Performance on dafs at a wedding in Khorog

More information on Pamiri musical instruments can be found on https://www.iis.ac.uk/view_article.asp?ContentID=106106.

The following website https://www.gildedserpent.com/cms/2009/09/30/robyntajikistan/ contains a fascinating account of a visit to the Bartang valley by Dr. Robyn Friend, director of the Institute of Persian Performing Arts, based in Los Angeles, to study Pamiri music and dancing. N.B. The Bartang valley is one of the few remaining places where genuine spontaneous Pamiri music and dance can still be experienced – get there before television becomes the main domestic leisure activity.

A very interesting doctoral thesis by Benjamin Koen at the University of Ohio (Devotional music and healing in Badakhshan, Tajikistan: preventive and curative practices) together with samples (wav files) of Pamiri music can be found on https://www.ohiolink.edu/etd/view.cgi?acc_num=osu1059673277

Other information resources:

Pre-Islamic:

https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/culture/religion/religion.html

Islam and Ismailism:

https://www.akdn.org/about_imamat.asp

https://www.iis.ac.uk

Buddhism in Central Asia:

https://www.berzinarchives.com/e-books/historic_interaction_buddhist_islamic/history_cultures_01.html

Zoroastrianism:

https://www.angelfire.com/rnb/bashiri/Zorobar/Zorobar.html

https://www.zoroastrianism.com/

For Pamiri hats and other handicrafts:

https://www.textile-art.com/geb.html

For ancient and contemporary Tajik design:

https://www.arzhang.tajik.net/index.html

General

https://www.angelfire.com/sd/tajikistanupdate/culture.html

Shrines

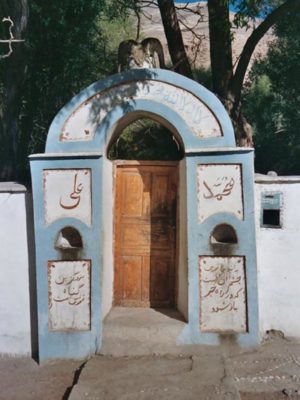

Gorno-Badakhshan has a wealth of shrines (‘Mazar’, pronounced locally ‘Mazor’) and sacred places (‘Oston’) dedicated to holy men. The majority of these are venerated by the Ismaili community in the Pamirs, but there are also shrines in Sunni villages – for example, the picture below is from the village of Poi-Mazar at the upper end of the Vanch valley – a region in which the population is almost totally Sunni – showing what, according to legend, is the grave of Ali.

The shrines of Gorno-Badakhshan are characterised by the presence of sacred stones and the horns of ibex and Marco Polo sheep (Ovis Poli), symbols of purity under Aryan and Zoroastrian religious traditions, long before the introduction of Islam; they also show evidence of regular use for fire rituals, in which aromatic herbs (‘strachm’ or ‘yob’) and animal fat (‘roghan’) are burnt. The local traditions and legends attached to some shrines also pre-date the introduction of Islam in the Pamirs.

This section has been put together with the kind assistance of Professor Jo-Ann Gross, of the College of New Jersey, who is currently preparing a scholarly study of Tajik shrines. A non-exhaustive list of shrines in Gorno-Badakhshan follows, the more interesting of which are shown in bold. N.B. The name of the village is followed by the name of the shrine(s) there.

Professor Gross subdivides the shrines of Badakhshan in the following categories:

– sacred places associated with nature, including hot and/or mineral springs, large or unusual trees, caves, and rock formations;

– shrines where eminent religious figures are buried (Ismaili pirs, khalifas, or Sufis);

– shrines in places where eminent religious figures are believed to have visited in the past (including figures from early Islamic history such as ‘Ali or Muhammad Baqir);

– sacred places where animals carrying early Islamic figures passed or are believed to have left footprints in the ground or rock.

Prominent at most shrine sites are collections of animal horns and special stones, which also have sacred properties. In general, rituals associated with sacred places are reserved for special holidays such as Navruz or Eid-e Qurbon, rather than the previous practice of weekly Friday village gatherings. The photographs that accompany the list illustrate these features.

Darwaz District

Yoged: Ostoni Khoja Khizr, Ostoni Shah Owliyo, Ostoni Khoja Chiltan, Ostoni Khoja Nazar

Vanch District

Poi Mazar: Sardi Saïd, Sardy Bard, Abdulkakhori Sarmast

Vanvan: Khotchai Sabz Poosh

Ubaghn: ‘Alexander’s tomb’

Shugnan District

Porshnev: Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadoni – Kushk, Sumbi Duldul – Barchiddara

Gumbazi Pir Sayyid Farukhshoh – Saroi Bakhor (above)

Piri Shohnosir – Midenshor

Tem: Imom Zaynulobidin

Sokhcharv: Piri Dukman

Suchon: Shohi Viloyat

Sijd: Shohmalang

Ver: Sumbi Duldul

Vankala: Imom Muhammad Bokir

Roshtkala District

Tavdem: Oston and mazor of Sayyid Jalol

The recent renovation was intended to preserve rather than rebuild the original shrine: special care was taken to build a new protective structure outside of the original and the old earthen, and stone shrine with carved wooden beams thus remains undisturbed.

Tusyon: Shoh Burhoni Vali

Khichikh: Sho Burhon

Parshed: Khojai Zur

Bodom: Khojai Nur (sister of Khojai Zur), Sumbi Duldul

Baroj: Shoh Burhon

Nimoth: Sho Abdol (Imom Bokir)

Barboz: Ostoni Piri Fokmammad

Rushan District

Vomar: Ostoni Sayyid Jalol

Yemts: Mushkilkusho

Bassid: Khazrati Khojai Nuruddin (below); Safdaron.

Rushan District

Vomar: Ostoni Sayyid Jalol

Yemts: Mushkilkusho

Bassid: Khazrati Khojai Nuruddin (below); Safdaron.

Bardara: Farmon (below).

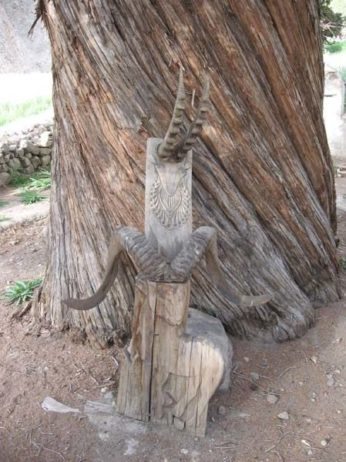

Bardara is tucked away at the top of a narrow valley with splendid views of the mountains beyond. The name of the shrine comes from the ‘farmon’ (firman) sent by Imam Sultan Mohamed Shah (Aga Khan III) to confirm receipt of offerings from Bardara – a document still kept in the village. The shrine is located in the centre of a row of three very old juniper trees, exactly 508m apart.

In other parts of Gorno-Badakhshan there are old sacred juniper trees identical to those in Bardara, such as the one on the windswept plain above Roshorv in Bartang – see below. Its presence is a mystery – it is the only tree growing at this location and was once part of a group of three identical trees, equidistant and aligned, just as in Bardara, in a NNW-SSE direction.

According to one legend, they were planted by Ali to mark the route he took through the Pamirs. According to another, they were planted by Nasr Khusraw for the same reason.

Roshorv: Borkhatsij, Sho Tolib, Sho Husein, Andrim

Savnob: Hozirbosht (left), Khojai Hizr, Mahfiloston, Hazrati Daoud

‘Hozirbosht’ means ‘be prepared’ and the shrine is not far from a cave complex that served in the past as a refuge for women and children during the occasional raids by Kyrgyz maruaders.

Yapshorv: Khojai Shayuz

Nisur: Sho Husein, Pir Nosir, Hazrat Daoud

Khuf: Mustansiri Billoh

Yomj: Ostoni Shohtolib

Ishkashim District

Shambedeh: Ostoni Shohburhon

Rin: Ostoni Zanjiri Kaba

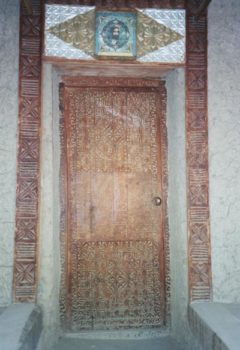

Namadgut: Ostoni Shohi Mardon (above)

The outer gate to the mazor itself is covered in calligraphy and the door to the mazor is a good example of early wood carving. This mazor has an amazing garden filled with old twisted sacred trees, including huge plane trees. A trip to Ptup is highly recommended, since in addition to the mazor, there is also, above the village, the sacred hot springs Bibi Fotima and the spectacular fortress Zulkhomor in Yamchun.

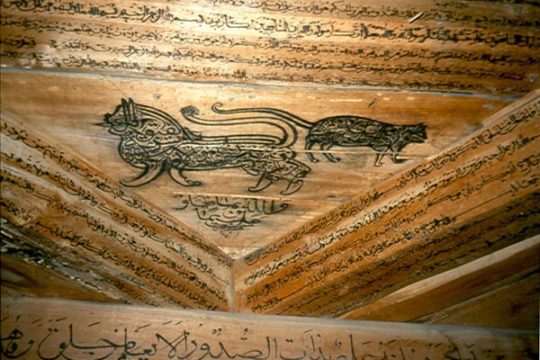

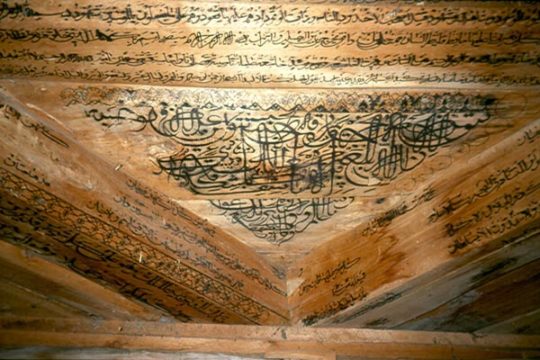

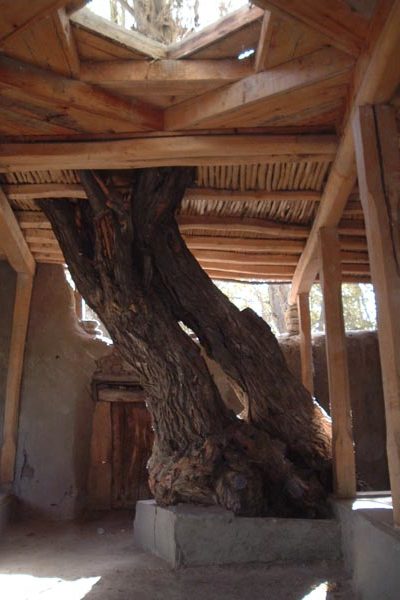

Yamg: Osorkhonai (and museum) Sufi Muborakkadam (above).

This is the former residence of Sufi Muborakkadam, a famous 19th century philosopher and astronomer, and has superb carved pillars and beams, as well as his manuscripts and the solar stone he used for determining the seasons.

Ostoni Gesuv (above)

Zugvand: Ostoni Panjai Shoh

Langar: Mazori Shohkambari Oftob (above).

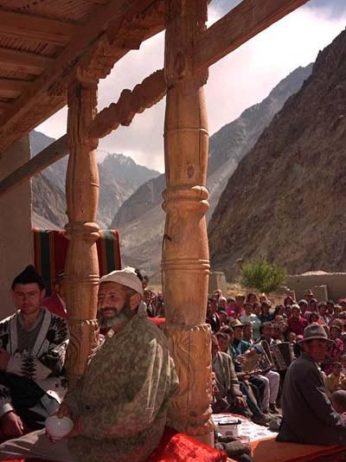

Opposite the mazor there is a Pamiri guesthouse and museum with richly carved beams and pillars – worth an overnight stay there (below).

Hisor: Ostoni Nuri Muhammad

In addition there are a number of small roadside shrines, especially in the Wakhan – above: shrines in Zumudg and Vnukut (‘Chil Murid’ – ‘forty faithful’). Finally, although not strictly speaking a shrine, the (Sunni) mosque in Shaimak (Murghab district – below), built only some fifty years ago, has an unreal Disneyland quality – worth a visit, if in Murghab, for the spectacular scenery of the Aksu river and views of the Little Pamir.