One of the most important repositories of the culture of the Pamirs is the traditional Pamiri house, locally known as ‘Chid’. It embodies elements of ancient Aryan philosophy – including Zoroastrianism – many of which have since been assimilated into Pamiri Ismaili tradition. What to the untrained eye looks like a very basic – even primitive – structure, is, for the people who live in it, rich in religious and philosophical meaning. The symbolism of specific structural features of the Pamiri house goes back over two and a half thousand years.

The house itself is the symbol of the universe and also the place of private prayer and worship for Pamiri Ismailis – the Ismailis have as yet no mosques in Gorno-Badakhshan. The layout of the house is as described below, although some houses have a mirror-image of what is described.

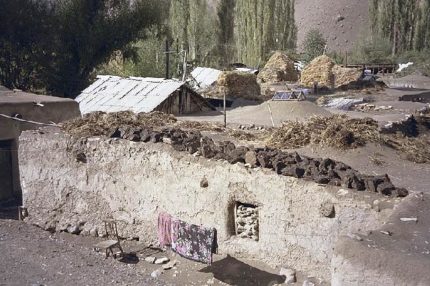

The Pamiri house is normally built of stones and plaster, with a flat roof on which hay, apricots, mulberries or dung for fuel can be dried.

House in Andarob (Ishkashim district).

The skylight can be seen on the roof.

Inside, most houses comprise a small internal lobby – frequently used for sleeping or eating in the summer months – and a large square room, entered through a door in the lobby. Beyond this door is the main room, entered through a small corridor (with space to the left and right for washing and storage); the corridor leads into an open area comprising the following standard elements:

a) Three living areas (‘Sang’, or ‘Sandj’), symbolising the three kingdoms of nature: animal, mineral and vegetable: the floor (‘Chalak’), normally of earth, where the fire (or more frequently today, a cast-iron oven) burns, corresponds to the inanimate world; the first raised dais (‘Loshnukh’) corresponds to the vegetative soul; and the third floor level (‘Barnekh’) to the cognitive soul.

b) Five supporting pillars, symbolising the five members of Ali’s family: Mohamed, his son-in-law Ali, Mohamed’s daughter Bibi Fatima (Ali’s wife), and their sons Hassan and Hussein – it has been suggested that in Zoroastrian symbolism the pillars may have corresponded to the major gods/goddesses (‘Yazata’ or ‘Eyzads’): Surush, Mehr, Anahita, Zamyod and Ozar. The number five also reflects the five principles of Islam.

1. The pillar symbolising the prophet Mohamed (‘Khasitan-Shokhsutun’), to the left of the entrance, was traditionally made of juniper – a sacred tree and symbol of purity, the smoke of which has healing and disinfectant properties; today, there are no longer enough junipers of adequate size for making this pillar in newly constructed houses. The child’s cradle will normally be put close to this pillar.

'Ali' pillar in the museum

'Ali' pillar in the museum in Langar in the Wakhan, showing Zoroastrian sun symbols

2. The pillar symbolising Ali (‘Vouznek-sitan’) is situated diagonally left from the entrance. In Zoroastrian tradition, this pillar corresponded to the angel of love (‘Mehr’). At weddings, the bridal couple will be seated at this pillar, in the hope of being blessed with good fortune and happiness (‘Barakat’). Tradition requires that – in addition to her own father and father-in-law – the bride must have a third father, the person who, at this pillar, ritually uncovers her face from seven veils during the wedding ceremony.

3. Diagonally right from the entrance is the pillar symbolising Bibi Fatima (‘Kitsor-sitan’). It is the place of honour for the bride at the engagement ceremony and her engagement dress corresponds to the traditional perception of Fatima (and the goddess Anahita): red dress, bracelets, rings, ear-rings. In Zoroastrian tradition, this column corresponded to the angel who guarded the fire. The stove or family fire is closest to this pillar and it serves also for fire-related rituals.

Interior of a Pamiri house in Roshtkala

in the foreground the 'Fatima' pillar, then - background clockwise - the pillars symbolising 'Ali', 'Mohamed' and 'Hussein'

4/5. The fourth (Hassan) and fifth (Hussein) pillars are joined to show the closeness of the relationship between Hassan and Hussein. The crossbar is carved with Zoroastrian symbols, frequently including a central depiction of the sun, and is sometimes decorated with the horns of a Marco Polo sheep (Ovis poli).

The ‘Hassan’ pillar (‘Poiga-sitan’) is the place of family and private prayer and is considered the place of honour for the religious leader (‘Khalifa’) or a chief guest. The chief guest will normally leave a small symbolic space next to him/her against the pillar showing that it is reserved for the Khalifa. In Zoroastrian tradition, this pillar may have personified ‘Zamyod’.

Mourning ceremonies – with a ritual lamp or candle lit for three days – are carried out close to the ‘Hussein’ pillar (‘Barnekh-sitan’). In Zoroastrian tradition this pillar could have been associated with ‘Ozar’.

c) Two main transversal supporting beams – one across the ‘Mohamed’ and ‘Ali’ pillars, one across the ‘Fatima’ and ‘Hassan/Hussein’ pillars. For Pamiri Ismailis, the first symbolises universal reason (‘Akli kul’), and the second the universal soul (‘Nafsi kul’). In Zoroastrianism, the two beams corresponded to the material and spiritual worlds.

d) Several groups of beams. The total number varies according to the size of the house and local interpretation of Pamiri tradition. There are several different theories concerning their number. For some the total must be the number of Ismaili Imams (49), for others they are equal to the number of Ali’s Army, when they were killed in Dashti Karbalo (72). In most cases, there are thirteen intermediary beams: six – over the fireplace – representing Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus and Mohamed, the six prophets revered in Islam (in Zoroastrianism the number six could relate to East, West, North, South, Upper, Lower); and seven representing the first seven Imams. In Zoroastrianism the number seven relates to the main heavenly bodies (Sun, Moon, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Venus and Mercury) and the seven principal Amesha Spentas or ‘Holy Immortals’). The Ismailis are ‘sevener’ Muslims: for them Ismail was the seventh Imam.

Other beams on the ceiling may include groups of eighteen or seventeen beams corresponding to elements of Ismaili cosmogony.

e) A raised platform (approx. 50cm) around the inside walls of the house. Underneath the platform is a storage area, but – prior to the widespread introduction of metal stoves, which now stand in the open floor area – it would have incorporated the family hearth, as in the photo below.

Fireplace in the Sufi Muboraki

Fireplace in the Sufi Muboraki Vokhoni museum in Yamg (Ishkashim district)

f) A skylight, the design of which incorporates four concentric square box-type layers known as ‘chorkhona’ (‘four houses’) representing, respectively, the four Zoroastrian elements earth, water, air and fire, the latter being the highest, touched first by the sun’s rays.

Other decorative elements in a Pamiri house – in addition to the carved Zoroastrian symbols – frequently include a combination of red and white, symbolising respectively (in both Zoroastrianism and local Ismaili belief):

· Red: the sun, blood – the source and essence of life – and fire and flame – the first thing created by God;

· White: light, milk – the source of human well-being.

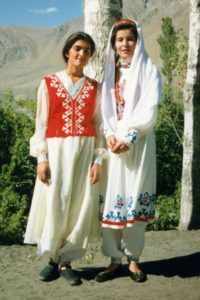

Traditional Pamiri dress

Traditional Pamiri dress also incorporates the colours red and white.

At the Persian New Year (‘Navrouz’), a willow wreath (in the form of a circle containing a cross) is dipped in flour and used to draw figures and designs on the walls and columns of the main room. Stripped willow twigs are bound together (to resemble a vegetable stalk) and placed between the beams as a token of abundant crops in the new year.

For the people of the Pamirs, willow is the symbol of new life, because in spring it is the first tree that “wakes up” after a long sleep. It plays a role in wedding ceremonies, when a willow twig is used to lift the bride’s veil and when an arrow made of willow is shot through the skylight. In old times when a husband wanted to divorce his wife, he took a stick of willow and broke it above her head.

At burials, a willow stick is used to measure the length of the body and determine the size of the grave to be dug.

See also: https://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/tajikistan/page4.htm.